Salmonella enteritidis in chickens

Обновлено: 24.04.2024

Wolfgang Rabsch*, Billy M. Hargis†, Renée M. Tsolis†, Robert A. Kingsley†, Karl-Heinz Hinz‡, Helmut Tschäpe*, and Andreas J. Bäumler†

Author affiliations: *Robert Koch Institute, Wernigerode, Germany ; †Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA ; ‡School of Veterinary Medicine, Hanover, Germany

Abstract

Salmonella Enteritidis emerged as a major egg-associated pathogen in the late 20th century. Epidemiologic data from England, Wales, and the United States indicate that S. Enteritidis filled the ecologic niche vacated by eradication of S. Gallinarum from poultry, leading to an epidemic increase in human infections. We tested this hypothesis by retrospective analysis of epidemiologic surveys in Germany and demonstrated that the number of human S. Enteritidis cases is inversely related to the prevalence of S. Gallinarum in poultry. Mathematical models combining epidemiology with population biology suggest that S. Gallinarum competitively excluded S. Enteritidis from poultry flocks early in the 20th century.

The avian-adapted serovar Salmonella Gallinarum, which includes two biovars, Gallinarum and Pullorum, was endemic in poultry flocks in Europe and the Americas in the early 20th century (1). To reduce economic losses to the poultry industry, national surveillance programs were established in the United States (National Poultry Improvement Plan, 1935) and England and Wales (Poultry Stock Improvement Plan, 1939). Since S. Gallinarum (antigen formula O9,12:-:-) has no animal reservoir other than domestic and aquatic fowl, the test-and-slaughter method of disease control under these surveillance programs led to its eradication from commercial poultry flocks in the United States, England, and Wales by the 1970s (1,2). At that time, the number of human cases of infection with serovar S. Enteritidis (antigen formula O9,12:g,m:1,7) began to increase in these countries (3,4). By the 1980s, S. Enteritidis had emerged as a major concern for food safety in Europe and the Americas (5); by 1990 it was the most frequently reported Salmonella serovar in the United States (6). Most S. Enteritidis outbreaks in Europe and the United States are associated with foods containing undercooked eggs (7-10). Eggs can become contaminated with S. Enteritidis through cracks in the shell after contact with chicken feces or by transovarian infection (11). Thus, laying hens were the likely source of the S. Enteritidis epidemic in Europe and the Americas.

The inverse relationship between the incidence of S. Gallinarum infection in chickens and egg-associated S. Enteritidis infections in humans prompted the hypothesis that S. Enteritidis filled the ecologic niche vacated by eradication of S. Gallinarum from domestic fowl (12). The hypothesis suggests that the epidemic increase in human S. Enteritidis cases in several geographic areas can be traced to the same origin, accounting for the simultaneous emergence of S. Enteritidis as a major egg-associated pathogen on three continents (5). A connection between the epidemics in Western Europe and the United States was not apparent from analysis of epidemic isolates. Although most human cases from England and Wales result from infection with S. Enteritidis phage type 4 (PT4), most cases in the United States are due to infections with PT8 and PT13a (13,14). The PT4 clone is genetically distinct from PT8 and 13a, as shown by IS200 profiling, ribotyping, and restriction length polymorphism of genomic DNA fragments separated by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (15). The reasons for the differing clonal isolates in the United States and Western Europe are unknown. S. Enteritidis was likely introduced into poultry flocks from its rodent reservoir (12). The geographic differences in predominant phage types may reflect the fact that at the time of introduction into poultry flocks, different S. Enteritidis strains were endemic in rodent populations in Europe and the United States. Subsequently, S. Enteritidis strains with the highest transmissibility may have become predominant in poultry flocks on each continent. An alternative explanation for the predominance of PT4 in England and Wales is its introduction into poultry breeding lines in the early 1980s (16), which may have accelerated the epidemic spread of PT4 in laying hens and resulted in its dominance in human isolates from England and Wales. However, factors responsible for the beginning of the S. Enteritidis epidemic should be considered separately from those important for its subsequent spread within the poultry industry. These factors were not specific to PT4 but rather allowed different phage types to emerge as egg-associated pathogens on different continents at the same time (5).

One such factor could be the eradication of S. Gallinarum from poultry, which would facilitate circulation of S. Enteritidis strains within this animal reservoir regardless of phage type. Experimental evidence indicates that immunization with one Salmonella serovar can generate cross-immunity against a second serovar if both organisms have the same immunodominant O-antigen on their cell surface (17-19). The immunodominant epitope of the lipopolysaccharide of S. Gallinarum and S. Enteritidis is the O9-antigen, a tyvelose residue of the O-antigen repeat (20). Immunization of chickens with S. Gallinarum protects against colonization with S. Enteritidis (21,22) but not S. Typhimurium, a serovar expressing a different immunodominant determinant, the O4-antigen (23). Theory indicates that coexistence of S. Gallinarum and S. Enteritidis in an animal population prompts competition as a result of the shared immunodominant O9-antigen, which generates cross-immunity. Mathematical models predict that the most likely outcome of this competition between serovars is that the serovar with the higher transmission success will competitively exclude the other from the host population (24-26). S. Gallinarum may have generated populationwide immunity (flock immunity) against the O9-antigen at the beginning of the 20th century, thereby excluding S. Enteritidis strains from circulation in poultry flocks (12). This proposal is based on analysis of epidemiologic data from the United States, England, and Wales. To formally test this hypothesis, we analyzed epidemiologic data from Germany to determine whether the numbers of human S. Enteritidis cases are inversely related to those of S. Gallinarum cases reported in poultry. We used mathematical models to determine whether our hypothesis is consistent with theoretical considerations regarding transmissibility and flock immunity.

Inverse relationship of S. Enteritidis and S. Gallinarum isolations in Germany

Figure. (A) S. Gallinarum infections in chickens in England and Wales (closed squares) (2,28) and the Federal Republic of Germany (open squares) (31). (B) Human cases.

In West Germany, the number of human S. Enteritidis cases was monitored by a national surveillance program (Figure) (Zentrales Überwachungsprogram Salmonella, ZÜPSALM)from 1973 to 1982. In 1975, the number of human infections began to increase, indicating the beginning of the S. Enteritidis epidemic in West Germany. In 1983 the ZÜPSALM program was replaced by a national program for surveillance of foodborne disease outbreaks (Zentrale Erfassung von Ausbrüchen lebensmittelbedingter Infektionen, ZEVALI), implemented by the Department of Public Health (Bundesgesundheitsamt). In the first year of this program, S. Enteritidis was responsible for 62 outbreaks, most of which were traced to raw eggs. By 1988, the number of disease outbreaks caused by S. Enteritidis had increased to 1,365.

In 1967 in England and Wales, poultry, particularly chickens, became the main human food source of S. Enteritidis (3). Before that date, the organism had only sporadically been isolated from poultry (3). A continuous increase in human S. Enteritidis cases was recorded from 1968 until the epidemic peaked in 1994 (12,16). Thus, the human S. Enteritidis epidemic in England and Wales probably began in 1968 after this organism became associated with a human food source, chickens. The rapid increase in the number of human cases from 1982 to 1988 was probably due to the introduction of PT4 into poultry breeding lines in England and Wales (16). Comparison of data from England and Wales (3,27) showed that S. Enteritidis emerged somewhat later in West Germany (Figure).

Eradication of S. Gallinarum was among the factors contributing to the emergence of S. Enteritidis as a foodborne pathogen (12). To determine whether delayed elimination of avian-adapted Salmonella serovars from commercial flocks contributed to the late start of the human epidemic in Germany, we compared the results of surveys performed in poultry flocks in Germany with those from the United Kingdom and the United States. Control programs in the 1930s triggered a steady decline in the incidence of S. Gallinarum in poultry flocks in the United States, England, and Wales (1,2,12). By the early 70s, only a few cases of S. Gallinarum were reported each year to veterinary investigation centers in England and Wales (28). In Germany, the first national survey performed by the Department of Public Health (Reichsgesundheitsamt) in 1929 showed that 16.3% of birds were seropositive for S. Gallinarum (29). Blood-testing performed 20 years later with 6,313 birds in a province (Südbaden) of West Germany still detected 19.5% reactors (30). This high prevalence of S. Gallinarum in 1949 likely reflects the fact that after World War II available resources were directed toward rebuilding the poultry industry rather than improving disease control. The comparatively slow decline in the prevalence of S. Gallinarum in West Germany is illustrated further by data for cases of disease reported from poultry. The number of S. Gallinarum isolations from chicken carcasses received by veterinary laboratories in West Germany was reported by a surveillance program from 1963 to 1981 (31). During this period, the rate of decrease in numbers of S. Gallinarum cases in England and Wales was considerably higher than that reported from West Germany (Figure). In each country the numbers of S. Gallinarum cases were inversely related to the numbers of human S. Enteritidis cases. These data are consistent with the concept that the relative delay in eradicating S. Gallinarum from poultry may have contributed to delayed onset of the S. Enteritidis epidemic in West Germany.

Competitive exclusion of S. Enteritidis by S. Gallinarum

To calculate whether the prevalence of S. Gallinarum in chickens was high enough to generate flock immunity against S. Enteritidis, we analyzed epidemiologic data by mathematical models combining epidemiology with population biology (24-26). The transmission success of a pathogen is measured by the basic case-reproductive number, R0, which is defined as the average number of secondary cases of infection from a primary case in a susceptible host population (32). In direct transmission, the basic case-reproductive number of a pathogen is directly proportional to the duration, D, for which an infected host can transmit the disease before it is either killed or clear of infection; the probability, ß, by which the disease is transmitted from an infected animal to a susceptible host; and the density of susceptible hosts, X (24).

R0=ßDX (equation 1)

After a pathogen is introduced into a susceptible host population, the reproductive rate of the infection declines as a consequence of the removal of a fraction, y, of the susceptible population, X, either by disease-induced death or acquisition of immunity. That is, the effective case-reproductive number, R, will be smaller than the basic case-reproductive number R0.

R = ßD (X-Xy) = R0-R0y (equation 2)

In an endemic state, each primary case of infection produces, on average, one secondary case. Thus, the effective case-reproductive number in a steady endemic-state situation is R=1. By solving equation 2 for R0, we obtain (33)

R0=1/(1-y) (equation 3)

Since S. Gallinarum was endemic in poultry populations at the beginning of the 20th century, its basic case-reproductive number, R0, can be calculated on the basis of epidemiologic data collected before control measures were implemented, by estimating the fraction, y, of birds removed from the susceptible population.

The first method developed for detecting anti-S. Gallinarum antibodies was a macroscopic tube agglutination test introduced in 1913 (34). In 1931, the tube agglutination test was partially replaced by the simpler whole-blood test for slide agglutination of stained antigen (35). Initial surveys performed from 1914 to 1929 revealed that on average 9.8% to 23.8% of poultry in Europe and the United States were positive by the tube agglutination test (1,29,36). These data do not provide a direct estimate of the number of immune animals, since both serologic tests are relatively insensitive (37). However, the number of susceptible birds can be estimated by comparing results of serologic surveys with data from vaccination experiments. Immunization with S. Gallinarum vaccine strain 9R produces antibody levels high enough to be detected by the whole-blood tube or slide agglutination tests in only a small number of birds (approximately 10%) (20,23). The number of birds protected against challenge with virulent S. Gallinarum after a single oral or subcutaneous vaccination is considerably higher (approximately 60%) (23,38). The tube or slide agglutination test results (9.8% and 23.8% of birds, respectively, tested positive) at the beginning of this century suggests that at least 60% were immune to S. Gallinarum. In addition to acquired immunity, deaths, which likely occurred in most chicken flocks since S. Gallinarum reactors were present on most farms at the time, also reduced the density of susceptible hosts. For instance, only 9 of 144 farms surveyed in Hungary in the 1930s had no S. Gallinarum-positive birds (39). The death rates reported from natural outbreaks are 10% to 50%, although higher rates are occasionally reported (40). By the conservative estimate that 90% of birds in a flock will survive an outbreak and approximately 60% of the survivors will have protective immunity, the basic case-reproductive number, R0, of S. Gallinarum is estimated to be 2.8.

S. Enteritidis does not substantially reduce the density of susceptible animals by causing death. Thus, its basic case-reproductive number can be estimated from the number of birds that remained susceptible during the peak of the S. Enteritidis epidemic. Antibody titers in S. Enteritidis-infected flocks are generally too low to be detected by the tube or the slide agglutination tests (37,41), presumably because this serovar commonly colonizes birds without causing disease and consequently without triggering a marked immune response. Live attenuated S. Enteritidis aroA vaccine does not produce antibody titers detectable by the tube or the slide agglutination tests (42), and oral immunization with this aroA vaccine does not protect against organ colonization with wild type S. Enteritidis (43). Hence, exposure to S. Enteritidis does not protect at levels found in birds with previous exposure to S. Gallinarum. Indeed, in a survey of flocks naturally infected with S. Enteritidis, only one of 114 birds tested strongly positive by the slide agglutination test (37). Experimental evidence indicates that birds exposed to S. Gallinarum have strong cross-immunity against colonization with S. Enteritidis. For instance, immunization of chickens with a single dose of S. Gallinarum vaccine strain 9R causes similar levels of protection against challenge with S. Gallinarum (23,38) and S. Enteritidis (22,44). The high degree of cross-immunity suggests that the antibody titers detected by the tube agglutination test are predictive of protection against lethal S. Gallinarum infection and of immunity to colonization by S. Enteritidis. Applying the criteria used to calculate R0 for S. Gallinarum (10% reactors are indicative of 60% protection) to the S. Enteritidis data (37) suggests that approximately 5% of birds had protective immunity against this pathogen. From these data, the basic case-reproductive number of S. Enteritidis is estimated (R0=1.05) to be considerably lower than that of S. Gallinarum.

Several factors should be considered in interpreting these data. Our estimate of the R0 value for S. Enteritidis is based on epidemiologic data from the late 1980s. The intensive husbandry of chickens in the latter part of the 20th century has increased the density, X, of susceptible hosts and therefore R0 (equation 1). Furthermore, information on the number of birds in S. Enteritidis-infected flocks with positive reactions in the tube agglutination test is sparse, and data from the peak of the epidemic in 1994 are not available. The prevalence of S. Enteritidis in poultry has been documented by a survey performed in Lower Saxony, Germany, in 1993, a time when flocks were heavily infected. This study showed that 7.6% of 2,112 laying hens were culture positive at slaughter (45). Although this low prevalence is consistent with a low basic case-reproductive number of S. Enteritidis at the peak of the epidemic, these data cannot be used to derive a reliable estimate for the basic case-reproductive number of S. Enteritidis at the beginning of the 20th century. Given these limitations, the available epidemiologic evidence appears to be consistent with our hypothesis. From equation 2 (R=R0-R0y), we estimate that early in the century the number of susceptible birds killed by S. Gallinarum (assuming 100% cross-immunity and y = 0.65) reduced the effective case-reproductive number of S. Enteritidis to < 1 (R = 0.37). These estimates support the idea that at the beginning of the 20th century S. Gallinarum reduced the density of susceptible hosts sufficiently to competitively exclude S. Enteritidis from circulation in poultry flocks.

S. Enteritidis is unlikely to be eliminated from poultry by relying solely on the test-and-slaughter method of disease control because, unlike S. Gallinarum, S. Enteritidis can be reintroduced into flocks from its rodent reservoir. Instead, vaccination would be effective in excluding S. Enteritidis from domestic fowl because it would eliminate one of the risk factors (loss of flock immunity against the O9-antigen), which likely contributed to the emergence of S. Enteritidis as a foodborne pathogen. In fact, much of the decline in human S. Enteritidis cases in England and Wales since 1994 has been attributed to the use of an S. Enteritidis vaccine in poultry (16). However, serologic evidence that S. Gallinarum is more immunogenic than S. Enteritidis suggests that a more effective approach for eliciting protection in chickens would be immunization with a live attenuated S. Gallinarum vaccine. This approach would restore the natural balance (exclusion of S. Enteritidis by a natural competitor) that existed before human intervention strategies were implemented early in the 20th century.

Dr. Rabsch is a microbiologist at the National Reference Centre for Salmonella and other enteric infections at the Robert Koch Institute in Wernigerode, Germany. His research involves typing Salmonella isolates for epidemiologic analysis.

Инкубационный период при сальмонеллезе в среднем составляет 12-24 часа. Иногда он укорачивается до 6 часов или удлиняется до 2 дней.

Классификация

Этиология и патогенез

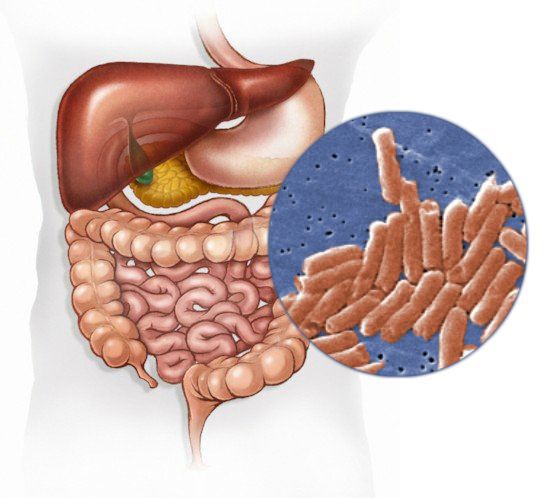

Возбудители сальмонеллеза относятся к роду Salmonella, семейству кишечных бактерий Enterobacteriaceae.

При попадании в желудочно-кишечный тракт сальмонеллы преодолевают эпителиальный барьер тонкого отдела кишечника и проникают в толщу тканей, где захватываются макрофагами. Внутри макрофагов бактерии не только размножаются, но и частично погибают, освобождая при этом эндотоксин, который поражает нервно-сосудистый аппарат кишечника и повышает проницаемость клеточных мембран. В результате сальмонеллы распространяются по лимфатическим путям и проникают в мезентериальные лимфатические узлы.

Помимо местного действия, эндотоксин оказывает влияние на развитие симптомов общей интоксикации организма. В этой стадии инфекционный процесс приобретает локализованную (гастроинтестинальную) форму и может завершиться. Возбудитель может поступать в кровь даже при локализованных формах инфекции, однако бактериемия Бактериемия - наличие бактерий в циркулирующей крови; часто возникает при инфекционных болезнях в результате проникновения возбудителей в кровь через естественные барьеры макроорганизма

при этом бывает кратковременной.

Повышение секреции жидкости в кишечнике возникает вследствие того, что сальмонеллезный энтеротоксин активирует аденилциклазу и гуанилциклазу энтероцитов с последующим нарастанием внутриклеточной концентрации биологически активных веществ (цАМФ, цГМФ и др.). Это влечет за собой поступление в просвет кишечника большого количества жидкости, калия, натрия и хлоридов.

У больных появляются рвота и понос, развиваются симптомы дегидратации и деминерализации организма, в сыворотке крови снижается уровень натрия, хлоридов и калия. В результате дегидратации возникает гипоксия тканей с нарушением клеточного метаболизма. В сочетании с электролитными изменениями это способствует развитию ацидоза Ацидоз - форма нарушения кислотно-щелочного равновесия в организме, характеризующаяся сдвигом соотношения между анионами кислот и катионами оснований в сторону увеличения анионов

.

В тяжелых случаях наблюдаются олигурия Олигурия - выделение очень малого по сравнению с нормой количества мочи.

и азотемия Азотемия - избыточное содержание в крови азотсодержащих продуктов белкового обмена

. Данные патологические явления наиболее выражены при развитии дегидратационного (чаще), инфекционно-токсического и смешанного шоков.

Эпидемиология

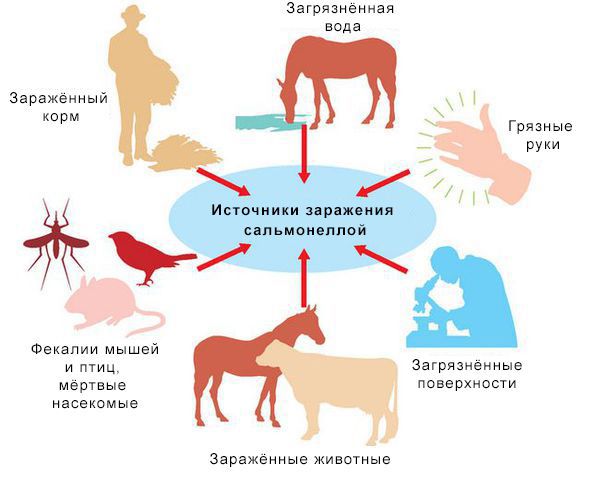

Источником инфекции могут являться животные и люди, при этом роль животных в эпидемиологии является основной.

У животных сальмонеллез встречается в форме клинически выраженного заболевания и бактериовыделительства. Эпидемиологическую опасность представляет инфицирование крупного рогатого скота, свиней, овец, лошадей, собак, кошек, домовых грызунов. Значительное место в эпидемиологии сальмонеллеза занимают птицы. Сальмонеллы обнаруживают в яйцах, мясе и внутренних органах птиц.

Механизм передачи возбудителей – фекально-оральный. Основной путь передачи инфекции – пищевой.

Сальмонеллез встречается в течение всего года, но чаще - в летние месяцы, что можно объяснить ухудшением условий хранения пищевых продуктов. Наблюдается как спорадическая, так и групповая заболеваемость этой инфекцией.

Факторы и группы риска

Клиническая картина

Cимптомы, течение

Сальмонеллезный гастрит - встречается редко. Клинические проявления:

- умеренные явления интоксикации;

- боли в эпигастральной области;

- тошнота;

- повторная рвота;

- поноса при этом варианте течения болезни не бывает.

Гастроэнтеритический вариант является наиболее частым клиническим вариантом сальмонеллезной инфекции. Характеризуется острым началом с появлением симптомов интоксикации и признаков поражения желудочно-кишечного тракта. Проявления достигают максимального развития в течение нескольких часов.

Во многих случаях отмечаются тошнота и рвота - чаще повторная, а не однократная, обильная, иногда неукротимая.

Стул жидкий, обильный, в основном сохраняет каловый характер, зловонный, пенистый, коричневого, темно-зеленого или желтого цвета. В некоторых случаях испражнения теряют каловый характер и могут напоминать рисовый отвар.

Живот, как правило, умеренно вздут. При пальпации отмечается болезненность в эпигастрии Эпигастрий - область живота, ограниченная сверху диафрагмой, снизу горизонтальной плоскостью, проходящей через прямую, соединяющую наиболее низкие точки десятых ребер.

, вокруг пупка, в илеоцекальной области; могут выявляться урчание, "переливание" в области петель тонкой кишки.

Гастроэнтероколитический вариант может иметь сходное с гастроэнтеритом начало, но далее в клинической картине все более отчетливо наблюдается симптомокомплекс колита Колит - воспаление слизистой оболочки толстой кишки

. В данном случае сальмонеллез по своему течению напоминает острую дизентерию.

Лихорадка при гастроинтестинальной форме сальмонеллеза может быть постоянной, реже - ремиттирующей или интермиттирующей. В некоторых случаях заболевание протекает при нормальной или субнормальной температуре.

В патологический процесс часто вовлекается поджелудочная железа. Повышается активность амилазы в крови и моче. Иногда появляются клинические симптомы панкреатита Панкреатит - воспаление поджелудочной железы

.

Диагностика

При гастроинтестинальной форме сальмонеллеза картина периферической крови различна:

- при большой потере жидкости развивается сгущение крови, возможен эритроцитоз;

- иногда развивается симптоматическая тромбоцитопения;

- количество лейкоцитов может быть различным – нормальным, сниженным, но чаще повышенным, особенно при тяжелом течении сальмонеллеза; обычно наблюдается умеренный лейкоцитоз, редко превышающий 20*10 9 /л;

- выявляется сдвиг лейкоцитарной формулы влево;

- СОЭ в пределах нормы или несколько увеличена.

В разгар болезни возможны нарушения водно-солевого обмена, приводящие к дегидратации и деминерализации организма. В самых тяжелых случаях наблюдаются сдвиги в кислотно-основном балансе.

Лабораторная диагностика

Ввиду полиморфизма клинических проявлений сальмонеллеза, лабораторное обследование больных является важным моментом в диагностике заболевания.

Бактериологические методы применяются для исследования рвотных масс промывных вод желудка, испражнений, дуоденального содержимого.

Дифференциальный диагноз

Наиболее часто гастроинтестинальную форму приходится дифференцировать от других острых кишечных инфекций - дизентерии, пищевых токсикоинфекций, эшерихиозов , холеры.

Нередко возникает необходимость дифференцировать эту форму от острых хирургических заболеваний – острого аппендицита, панкреатита, холецистита, тромбоза мезентериальных сосудов и острой гинекологической патологии – внематочной беременности и аднексита .

Также проводится дифференциация с терапевтическими патологиями - инфарктом, обострениями хронического гастрита, энтероколита, язвенной болезни.

Встречаются затруднения также при дифференциальной диагностике гастроинтестинальной формы сальмонеллеза и отравлений неорганическими ядами, ядохимикатами, грибами, некоторыми растениями.

Осложнения

Возможные осложнения при гастроинтестинальной форме сальмонеллеза:

- развитие сосудистого коллапса;

- гиповолемический шок;

- острая сердечная и почечная недостаточность.

Помимо этого, могут возникнуть пневмонии, восходящая инфекция мочевыводящих путей (циститы, пиелиты), токсико-инфекционный шок ("Сальмонеллезная септицемия" - A02.1, "Локализованная сальмонеллезная инфекция" - A02.2+).

Лечение

В настоящее время отсутствуют достаточно эффективные химиотерапевтические препараты (в том числе, антибиотики) для лечения гастроинтестинальной формы сальмонеллезной инфекции.

Главные направления патогенетической терапии при сальмонеллезе:

- дезинтоксикация;

- нормализация водно-электролитного обмена;

- борьба с гипоксемией , гипоксией, метаболическим ацидозом;

Прогноз

При гастроинтестинальной форме сальмонеллеза прогноз благоприятный, особенно в случаях ранней диагностики и правильного лечения.

Госпитализация

Переболевших выписывают после клинического выздоровления и отрицательных контрольных бактериологических исследований испражнений.

Профилактика

Ветеринарно-санитарные мероприятия:

- предупреждение распространения сальмонеллеза среди домашних млекопитающих и птиц;

- организация санитарного режима на мясокомбинатах и молочных предприятиях.

Цель санитарно-гигиенических мероприятий – предупреждение обсеменения сальмонеллами пищевых продуктов при их обработке, транспортировке и продаже.

В профилактике сальмонеллеза большое значение имеет правильная кулинарная и оптимальная термическая обработка пищевых продуктов.

Противоэпидемические мероприятия направлены на предупреждение распространения заболевания в коллективе. При возникновении спорадических заболеваний и эпидемических вспышек необходимо выявление путей передачи инфекции.

Sean F. Altekruse* , Nathan Bauer†, Amy Chanlongbutra*, Robert DeSagun*, Alecia Naugle*, Wayne Schlosser†, Robert Umholtz*, and Patricia White‡

Author affiliations: *US Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service, Washington, DC, USA ; †US Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service, College Station, Texas, USA ; ‡US Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

Abstract

US Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) data on Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis in broiler chicken carcass rinses collected from 2000 through 2005 showed the annual number of isolates increased >4-fold and the proportion of establishments with Salmonella Enteritidis–positive rinses increased nearly 3-fold (test for trend, p<0.0001). The number of states with Salmonella Enteritidis in broiler rinses increased from 14 to 24. The predominant phage types (PT) were PT 13 and PT 8, 2 strains that a recent Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) case-control study associated with eating chicken. FSIS is directing more sampling resources toward plants with marginal Salmonella control to reduce prevalence in products including broilers. The policy targets establishments with common Salmonella serotypes of human illness, including Salmonella Enteritidis. Voluntary interventions should be implemented by industry.

During the 1990s, Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis briefly surpassed S. Typhimurium as the predominant Salmonella serotype isolated from humans in the United States (1). Eggs were frequently implicated as the cause of outbreaks of human infection (2,3), and the outbreak strain was often detected in the implicated egg production flock (4). After egg producers implemented quality assurance programs in the late 1990s, human Salmonella Enteritidis infection rates decreased by ≈50% (1).

Recently, 2 US case-control studies in Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) sites identified eating chicken as a risk factor for sporadic human Salmonella Enteritidis infection (5,6), replicating findings of a case-control study performed in England in the late 1980s (7). While the overall incidence of human salmonellosis in FoodNet sites was lower in 2005 than in the mid-1990s, the incidence of Salmonella Enteritidis infections was ≈25% higher (8). We present US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) Salmonella testing program data collected from 2000 to 2005 that suggest a need for interventions to prevent the emergence of this Salmonella serotype in broiler chickens in the United States.

Methods

FSIS Salmonella Testing Program

As of January 2000, an FSIS performance standard for Salmonella was set for all establishments that slaughter US broiler chickens (9). Establishments that slaughtered >20,000 chickens per year were eligible for FSIS regulatory Salmonella testing. These establishments accounted for >95% of raw poultry marketed in the United States.

The sampling frame for the present study included all eligible FSIS-inspected establishments. Each month, eligible facilities were randomly selected for Salmonella testing to begin in the following month. In each broiler slaughter setting that was tested, 1 broiler chicken carcass rinse (hereafter referred to as broiler rinse) was collected per day for 51 days of operation. The 51 broiler rinses constitute a "Salmonella set." Sets were scheduled approximately once a year. When a plant did not meet the Salmonella performance standard, a follow-up set was scheduled. To limit bias, this report does not include data from follow-up sets.

Carcasses were collected after they exited the chiller, downstream from the slaughter line. The chiller is designed to bring carcass temperatures down to the refrigeration range. The postchill collection site was selected as the sampling site because interventions for pathogen reduction are generally located before this point.

Broiler Rinse Collection

Carcasses were collected after they exited the chiller and aseptically placed in a sterile bag. A 400-mL volume of buffered peptone water was added to the carcass in the bag. Half the volume was poured into the interior cavity and the other half over the skin. The carcass was rinsed with a rocking motion for 1 minute at a rate of ≈35 cycles per minute. After the carcass was removed from the bag, the rinse was poured into a sterile container and shipped on a freezer pack by overnight mail to 1 of 3 FSIS laboratories (Athens, GA; Alameda, CA; St. Louis, MO, USA) for analysis (10).

Microbiologic Testing

Testing of broiler rinses for Salmonella was performed by using standard FSIS isolation methods (11). Before October 2003, an immunoassay system (Assurance polyclonal enzyme immunoassay, BioControl Systems, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA) was used to screen enrichment broths for Salmonella. Beginning in October 2003, Salmonella gene amplification (BAX System PCR Assay, DuPont Qualicon, Wilmington, DE, USA) was performed on lysed cells after overnight incubation in buffered peptone broth (35°C). Broiler rinses that tested positive on the screening test were cultured for Salmonella with standard methods (i.e., selective enrichment, plating, serologic and biochemical confirmation). Three presumptive Salmonella colonies with the predominant colony form were selected from each plate for biochemical and serologic confirmation. One confirmed Salmonella isolate was sent to the National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL, USDA-APHIS-VS, Ames, IA, USA) for Salmonella serotyping (12).

Beginning in 2001, isolates of Salmonella Enteritidis were phage typed at NVSL (13). Because the predominant Salmonella Enteritidis phage types were clonal (6,14) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns were not available on all isolates during the study period, no further characterization of the isolates was performed for this report.

Analysis

Analysis was restricted to Salmonella sets performed in calendar years 2000–2005. A χ 2 test (2-sided) was used to test trends for annual percent of Salmonella Enteritidis isolates among Salmonella-positive broiler rinses and all analyzed broiler rinses, respectively. A χ 2 test for trend was also performed to assess the percent of establishments tested annually with Salmonella Enteritidis–positive broiler rinses, with subanalyses by establishment size. Approximately two thirds of establishments were large ( > 500 employees), one fourth were small ( 10 employees), and 5% were very small (

The number of positive broiler rinses per state was plotted on a US map that showed the geographic density of broiler chicken production by county for the year 2002 (15). Results were plotted for 2 periods: calendar years 2000–2002 and 2003–2005. Phage types of isolates were tabulated by year.

The present study preceded a new FSIS policy to control Salmonella. The new policy emphasizes improvement in Salmonella control in product classes that have not reduced Salmonella prevalence in the past decade, such as broilers, and focuses on plants that test positive for common serotypes of human illness, such as Salmonella Enteriditis (16).

Results

During the 6-year study period, 280 (0.5%) Salmonella Enteritidis isolates were recovered from 51,327 broiler rinses (Table 1). From 2000 to 2005, the proportion of Salmonella isolates that were Salmonella Enteritidis increased (test for trend, p<0.0001). The percentage of all broiler rinses that tested positive also increased (test for trend, p<0.0001).

During the 6-year study period, the proportion of Salmonella Enteritidis–positive establishments with multiple positive broiler rinses per year also increased significantly (p 4 positive broiler rinses per year (of 51 broiler rinse tests per set) increased, beginning in 2002.

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of Salmonella Enteritidis isolates in broiler rinses in the first and second half of the study period (2000–2002 vs. 2003–2005). Each blue dot represents 2 million broilers produced in.

From 2000 to 2002, Salmonella Enteritidis was isolated from broiler rinses in 14 states, compared with 24 states from 2003 to 2005 (Figure 2). Phage type (PT) 13 was predominant, accounting for half of all isolates, followed by Salmonella Enteritidis PT 8, which accounted for more than one third of isolates (Table 3). In 2005, the number of isolates that were PT 8 increased >3-fold compared with 2004.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study was a significant increase in the number of broiler chicken slaughter establishments with Salmonella Enteritidis–positive broiler rinses in the years from 2000 through 2005. The 90 slaughter establishments with positive rinses were dispersed across 24 states, reflecting the geographic distribution of the US broiler industry. During the study period, increases were seen in the proportion of both large and small establishments that had such positive broiler rinses.

Some caution is warranted when interpreting our findings. The purpose of the FSIS Salmonella program is to assess performance of individual establishments. The program is not designed to estimate national prevalence of poultry contamination because it does not fully account for production volume or regional or seasonal effects. Furthermore, samples are collected after slaughter processes that are intended to reduce carcass contamination. Nonetheless, the apparent emergence of Salmonella Enteritidis in broilers is noteworthy given the increase in human Salmonella Enteritidis infection rates in the United States (8) and recent findings that eating chicken is a new and important risk factor for sporadic infection (5,6). Additional epidemiologic studies are recommended to further elucidate the role of contaminated chicken in human Salmonella Enteritidis infections and estimate the extent of illness attributable to chicken. Retail food surveillance and laboratory subtyping studies (6) may also be valuable because they enable comparisons of human and poultry strains.

In this report, 2 Salmonella Enteritidis phage types, PT 8 and PT 13, accounted for most isolates from broiler rinses. In a recent FoodNet study, the association between Salmonella Enteritidis infection and eating chicken strengthened in analyses restricted to patients infected with these 2 phage types (6). The possible emergence of these phage types in broiler chickens suggests that industry should implement appropriate Salmonella Enteritidis controls for broiler chickens (17,18).

The present study preceded a new FSIS policy to control Salmonella in broilers that emphasizes common serotypes of human illness (16). As part of this effort, FSIS held 2 public meetings on Salmonella in broilers: 1 in Athens, Georgia, in August 2005 on controls before slaughter (preharvest), and another in Atlanta, Georgia, in February 2006 on controls in the slaughter plant (postharvest). Information from these meeting was used to prepare guidelines to help broiler plants control salmonellae (19). The agency is also monitoring progress of meat and poultry plants in controlling this organism. If, in July 2007, most plants (e.g., 90%) that manufacture a specific product (e.g., broiler carcasses) have not reduced the percentage of Salmonella tests that are positive to at least half the FSIS performance standard, the agency will consider actions to improve control of salmonellae. One option that FSIS is considering is to post Salmonella results on the web for product classes that have not made sufficient progress, listing data by plant name.

In the 1990s, successful voluntary quality assurance programs to control Salmonella Enteritidis were developed by the egg industry and state poultry health officials (20). Many of the interventions are adaptable to the control of this organism in broilers. For example, control points for the organism in broilers are likely to include monitoring and sanitation of breeding flocks, hatcheries, broiler flocks, and slaughter establishments. Serotype data that FSIS provides to plants on each isolate as part of its new Salmonella policy (16) may also assist plant officials to make informed SE risk management decisions.

Dr Altekruse is a veterinary epidemiologist in the Public Health Service assigned to the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. His research interests include characterization of Salmonella isolates from meat and poultry and reductions in indicator and pathogen counts during slaughter.

Acknowledgment

We thank the FSIS headquarters, inspection, and laboratory personnel and APHIS laboratory personnel who made the report possible.

Remember to follow the Clean, Separate, Cook, and Chill guidelines to help keep you and your family safe from Salmonella. Be especially careful to follow the guidelines when preparing food for young children, people with weakened immune systems, and older adults.

Don’t let Salmonella make you or your loved ones sick. Take a look at these five facts and CDC’s tips for lowering your chance of getting a Salmonella infection.

- You can get aSalmonellainfection froma variety of foods. Salmonella can be found in many foods, including sprouts and other vegetables, eggs, chicken, pork, fruits, and even processed foods, such as nut butters, frozen pot pies, chicken nuggets, and stuffed chicken entrees. Contaminated foods usually look and smell normal, which is why it is important to know how to prevent infection.

- Salmonellaalso can spread from animals to people and from people to people. Always wash your hands after contact with animals. Also wash your hands after using the toilet, changing diapers, or helping someone with diarrhea clean up after using the toilet. If you have a Salmonella infection, you should not prepare food or drinks for others until you no longer have diarrhea.

- Salmonellaillness is more common in the summer. Warmer weather and unrefrigerated foods create ideal conditions for Salmonella to grow. Be sure to refrigerate or freeze perishables (foods likely to spoil or go bad quickly), prepared foods, and leftovers within 2 hours (or 1 hour if the temperature outside is 90°F or hotter).

- Salmonellaillness can be serious and is more dangerous for certain people. Anyone can get a Salmonella infection, but some people are more likely to develop a serious illness, including children younger than 5, older adults, and people with immune systems weakened from a medical condition, such as diabetes, liver or kidney disease, and cancer or its treatment.

- Salmonellacauses far more illnesses than you might suspect. For every person with a Salmonella illness confirmed by a laboratory test, there are about 30 more people with Salmonella illnesses that are not reported. Most people who get food poisoning do not go to a doctor or submit a sample to a laboratory, so we never learn what germ made them sick.

Pets and other healthy animals, including those at petting zoos, farms, fairs, and even schools and daycares, can carry Salmonella and other germs that make people sick. The following tips will help you stay safe when it comes to our feathery, furry, and scaly friends.

Что такое сальмонеллез? Причины возникновения, диагностику и методы лечения разберем в статье доктора Александрова Павла Андреевича, инфекциониста со стажем в 14 лет.

Над статьей доктора Александрова Павла Андреевича работали литературный редактор Маргарита Тихонова , научный редактор Сергей Федосов и шеф-редактор Лада Родчанина

Определение болезни. Причины заболевания

Сальмонеллёз — это острое инфекционное заболевание желудочно-кишечного тракта с возможностью дальнейшей генерализации процесса (распространением заболевания по всему организму). Причина развития сальмонеллёза — различные серотипы бактерий рода Salmonella. К клиническим характеристикам сальмонеллёза относят синдром общей инфекционной интоксикации, синдром поражения желудочно-кишечного тракта (гастрит, энтерит), синдром обезвоживания, гепатолиенальный синдром (увелечение печени и/или селезёнки) и иногда синдром экзантемы (высыпания).

Возбудитель

семейство — кишечные бактерии (Enterobacteriaceae)

род — Сальмонелла (Salmonella)

Существует 7 подвидов (более 2500 сероваров). Наиболее актуальные серовары: typhimurium, enteritidis, panama, london.

Представлены следующей антигенной структурой:

- О-антиген (соматический, термостабильный);

- H-антиген (жгутиковый, термолабильный);

- К-антиген (поверхностный, капсульный);

- Vi-антиген (антиген вирулентности — степень способности штамма вызвать заболевание; является компонентом О антигена);

- М-антиген (слизистый).

К факторам патогенности (механизмам приспособления бактерий) относятся:

- холероподобный энтротоксин — интенсивная секреция жидкости в просвет кишки;

- эндотоксин (липополисахарид) — общее проявление интоксикации;

- инвазия — заражение.

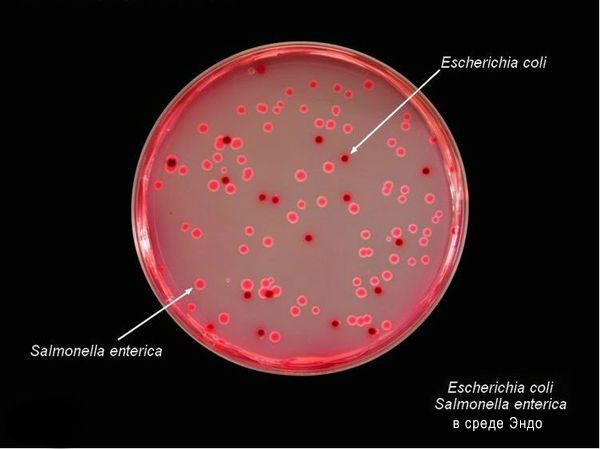

Тинкториальные свойства: разлагают глюкозу и маннит, образовывая кислоту и газ, продуцируют сероводород. Грамм-отрицательные палочки подвижны, спор и капсул не образуют. Растут на обычных питательных средах, образуя прозрачные колонии, на мясо-пептонном агаре с образованием колоний голубоватого цвета, на среде Эндо образуют прозрачные розовые колонии, на среде Плоскирева — бесцветные мутные, на висмут-сульфитном агаре — чёрные с металлическим блеском.

Высокоустойчивы во внешней среде (без агрессивных воздействий), активно размножаются в мясе и молоке (до 20 суток), в воде сохраняют жизнесособность до 5 мес., в почве — до 9 мес., в комнатной пыли — до 6 мес., в колбасе — до 1 мес., в яйцах — до 3 мес., в фекалиях сохраняются до 4 лет. При 56 °C погибают через 3 минуты, при кипячении мгновенно. Сальмонеллы, которые находятся в куске мяса массой 400 гр и толщиной до 9 см, погибают при его варке за 3,5 часа. Соление и копчение оставляет сальмонелл в живых. Воздействие кислот и хлорсодержащих дезинфицирующих средств вызывает их гибель. В последнее десятилетие появились штаммы сальмонелл, устойчивые ко многим антимикробным препаратам. [2] [5]

Эпидемиология

Зооантропоноз, распространённый повсеместно.

Источники инфекции: домашние животные (сами не болеют), птицы, человек (больной и носитель).

Резервуары инфекции и причина эпидемических вспышек сальмонеллеза: грызуны, дикие птицы, тараканы, улитки, лягушки, змеи.

Механизм передачи: фекально-оральный (пути — алиментарный, т. е. через органы ЖКТ, водный, контактно-бытовой). В основном источниками заражения являются птицы, яйца и молочные продукты. Инфицирующая доза 10*5-10*8 микробных тел.

Факторы риска

- детский возраст до 5 лет;

- возраст до 12 месяцев, особенно высока вероятность заболеть без грудного вскармливания;

- иммунодефицит (в основном у младенцев и лиц старше 65 лет, а так же у пациентов с ВИЧ в стадии СПИДа, принимающих иммунодепрессивные препараты);

- регулярный приём препаратов, снижающих кислотность желудка;

- употребление сырого и недостаточно термически обработанного мяса, молочных продуктов и яиц;

- частый контакт с животными с несоблюдением правил гигиены;

- посещение стран с низким уровнем жизни.

В России в 2016 г. заболеваемость была – 26 на 100 тыс. населения, у детей в до 14 лет – 71 на 100 тыс. Для сравнения в США среднегодовая заболеваемость — 15 на 100 тыс. (1,35 миллиона заболеваний, 26 500 госпитализаций и 420 смертей ежегодно). Иммунитет строго типоспецифичен (возможно многократное инфицирование различными штаммами) и непродолжителен [2] [6] [9] [10] .

При обнаружении схожих симптомов проконсультируйтесь у врача. Не занимайтесь самолечением - это опасно для вашего здоровья!

Симптомы сальмонеллеза

Инкубационный период — от 6 часов (при алиментарном заражении) до 3 суток. При внутрибрюшном заражении (искусственно) — до 8 дней.

Начало заболевания острое (т. е. развитие основных синдромов происходит в первые сутки заболевания).

Читайте также: